[ad_1]

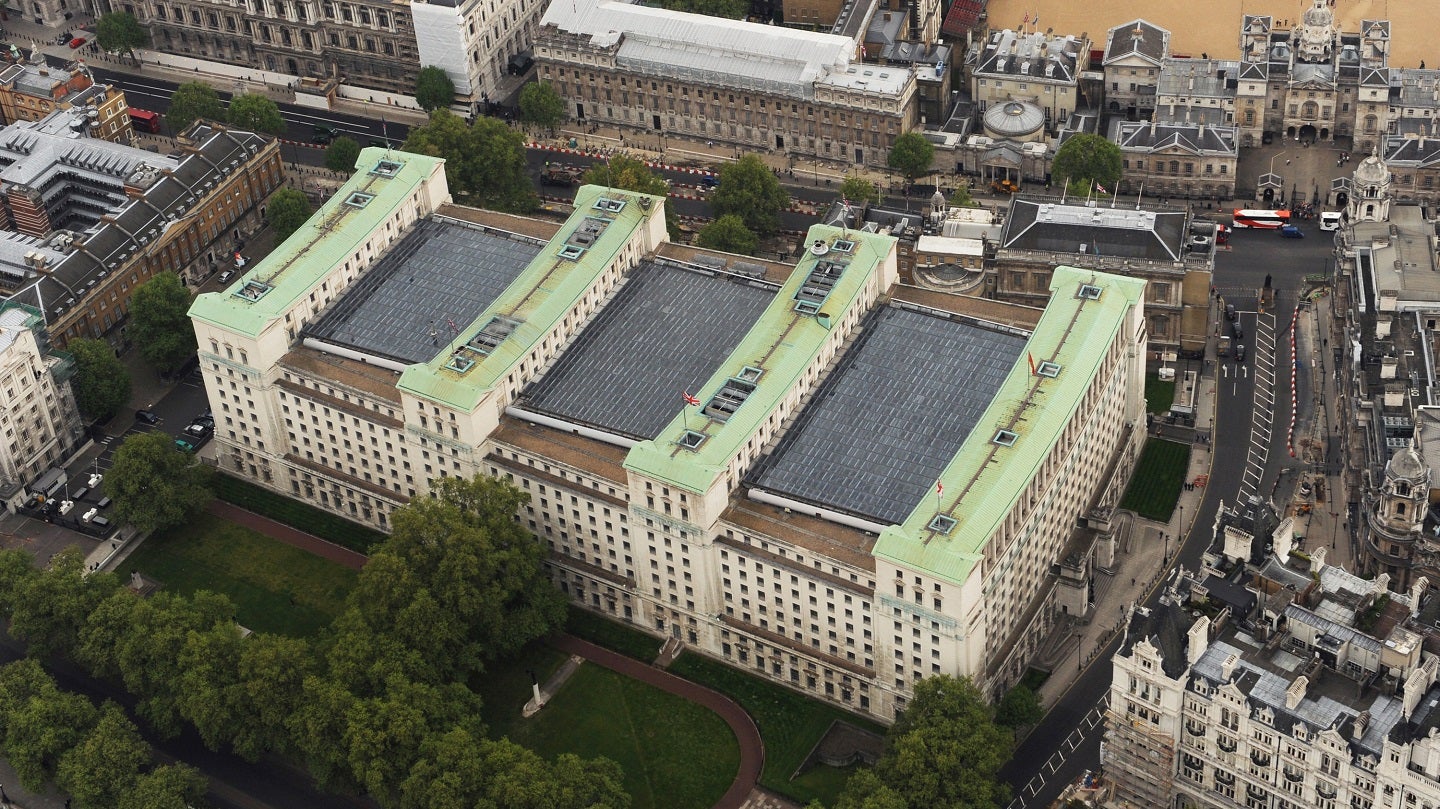

As if predicting, sage-like, the transit of the stars through the heavens, the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) has said the most important lesson to learn from the Defence Command Paper (DCP) refresh, rewritten in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, was that it got it right the first time around.

Published on 18 July just prior to the UK parliamentary summer recess, the DCP refresh (dubbed DCP 2023) was unusually keenly awaited for a House of Commons that does not hold defence up as one of the great offices of state, rather often treating it as one might an onerous domestic chore. However, the return of large-scale conventional warfare to the European continent focused minds into the sector as never before.

The suggestions as to what might be the outcome of the DCP refresh were rife, would there be more tanks, more armoured vehicles, perhaps even a reduction or halt in personnel cuts? Not really.

Contained in the Ministerial Foreward of the 90+ page document was the stance taken by Secretary of State for Defence Ben Wallace and Minister for the Armed Forces James Heappey, whose keystone missions – to “protect the nation and help it prosper”, was clear.

“That does not just mean more ships, tanks and jets – indeed in this document there are deliberately no new commitments on platforms at all – because on that we stand by what we published in 2021. Instead, we focus on how to drive the lessons of Ukraine into our core business and to recover the warfighting resilience needed to generate credible conventional deterrence,” the ministers stated.

Back to the future: DCP 2021 vs 2023

Published alongside the UK Government’s Integrated Review (IR) in 2021, the original DCP rode the crest of a defence wave with commitments of a further £5bn ($6.5bn) in the sector over two years, along with an aspiration that the country will spend 2.5% of GDP on defence over the longer term, albeit with the “when the economic and fiscal conditions allow” caveat.

A subsequent Integrated Review Refresh 2023, published in March of this year, identified the transition “to a multipolar, fragmented and contested world” had happened “more quickly and definitively” than anticipated in IR 2021.

An 18 July UK Government release regarding DCP 2023 stated it was “right to make the commitments” that were made in the 2021 iteration, with the UK “leading the way” in Europe on support for Ukraine’s defence and remaining a leader contributor to Nato. The 2021 versions of the IR and DCP had both stated Russia as being as “the most acute direct threat to the UK”, even prior to Moscow’s invasion of its neighbour.

In terms of equipment, the original DCP had set out “comprehensively” how the UK would design and equip its forces for the decades ahead, with the “majority” of these plans left unchanged in the 2023 version. Instead, areas such as improving how the MoD operates with its personnel, “kickstarting” a new relationship with the private defence sector, increasing productivity, and putting science and technology “at the heart of our force design and capability development”.

The DCP 2023 also sought to focus on investment in strategic enablers, infrastructure, and ammunition stockpiles necessary to maintain a credible defence resilience. A considerable portion of UK defence support to Ukraine since February 2022, which will top £4.6bn by the end of 2023, has been in the provision of ammunition, such as the Storm Shadow cruise missile and famed NLAW, which garnered a considerable number of column inches in the early stages of the conflict.

However, a number of UK parliamentarians have raised concerns about the UK’s own stockpiles of weapons, which had been hollowed out and hit by long lead times for replacements and inactive production lines.

Acquisition reform: the real change?

Despite the lack of additional platforms in the land, sea, and air, or indeed space, one potential inclusion could be the most important of the DCP 2023: that of acquisition reform.

The UK MoD has long been targetted as a department that fails to spend its considerable budget (in excess of £45bn in 2021/2022) in an efficient manner, leaving European partners such as France as apparently getting more bang for their buck. Rather, practices would be put in place to ensure that programmes are delivered faster, using more open architecture and spiral development.

“The experience of Ukraine has reminded us that accepting 80% can deliver effective and robust capability into the hands of the users today. Waiting for 100% – the exquisite solution – may mean losing strategic advantage,” the DCP 2023 states.

To this end, the MoD will look to set a maximum five-year commitment for acquisition programmes, with a maximum three-year commitment for those in the digital sector.

Such glaring lack of foresight and financial mismanagement severely undermines the credibility of the MoD’s forward-looking R&D efforts

Tristan Sauer, GlobalData

Potential early examples of developing or delivering platforms or capabilities at the speed of relevance can be seen in the British Army’s Project Wolfram, which appears to be exploring ways to provide a medium-range mobile fires solution through the combination of Brimstone missile modules fitted to flatbed stuck. This exact configuration was seen to be utilised by Ukrainian forces against Russia.

In addition, a new Integrated Design Authority (IDA) will “work with allies and across the defence industrial sector” to create “open standards” for UK defence platform operating systems. The principle aim of the IDA will be to “optimise UK defence integration”.

Analysis of DCP 2023: failure and dissonance

Tristan Sauer, aerospace and defence analyst at GlobalData, said that the priorities and objectives outline in DCP 2023 “only serve to highlight the failures” in both procurement and sustainment of critical capabilities over the last several years.

“Assertions that the MoD will invest over £6.6bn in advanced R&D efforts to ‘seize opportunities the opportunities presented by new and emerging technologies’ lack a certain gravitas in the face of mounting evidence of wasted capital,” Sauer detailed.

A prime example of such waste, according to Sauer, could be seen in the Warrior infantry fighting vehicle (IFV) Capability Sustainment Package which was scrapped in 2021 after over £431m of the total £750m budget was spent with a single platform receiving any upgrades.

A subsequent £20m tender for rear safety cameras for the Warrior IFV was a “retroactive attempt” to sustain the Warrior fleet which is set to begin its departure from service from 2025.

“Such glaring lack of foresight and financial mismanagement severely undermines the credibility of the MoD’s forward-looking R&D efforts, as key industry partners may prove less willing to participate in certain large-scale R&D efforts without sufficient guarantees on future procurement,” Sauer said.

Further, the DCP’s focus on enhancing the capabilities of human assets “further highlights the dissonance between policy and practice”, with the maintenance of force levels in line with the 2021 original creating an “upskilling” requirement that will provide additional burdens to personnel already weighed down with responsibilities.

This process, according to Sauer, demonstrated a “complete failure” to appreciate the risks engendered by increasing the burden on existing service personnel. This impact would be compounded with the MoD’s focus on increasing its use of autonomous vehicles, AI, and quantum computing, envisaged as ‘force multipliers’ in the future battlespace.

“Indeed, as the MoD looks to replace human assets with digitised solutions, the heightened cognitive burden and training requirements to ensure each servicemember has the requisite capacity to leverage those solutions effectively will likely prove detrimental to the efficiency and economic sustainability of the UK armed forces over the next decade,” Sauer explained.

Who will implement the change?

Although the joint signatory of the DCP 2023, Secretary of State for Defence Ben Wallace will not be charged with the initial implementation of its more sizeable reforms following his announced intention to leave the UK Government at the next Cabinet reshuffle and step down as an MP ahead of the next General Election in 2024.

Who exactly will be responsible for ensuring the aims of DCP 2023 are realised is as yet unclear, with a number of potential candidates, not least of which could be the document’s other signatory, Armed Forces Minister James Heappey.

[ad_2]