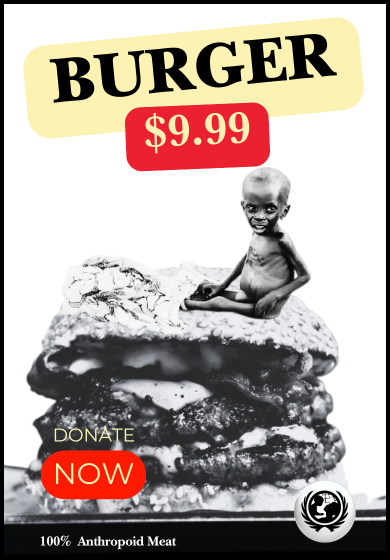

They could pay for the basic needs of the world’s 230 million most vulnerable people and still have the equivalent of the GDP of The Gambia left in their pocket.

The understanding that the 21st century is dominated by big corporations and the interests of a few wealthy people is no news. So it should come as a surprise to none of us if giant corporations were caught profiteering off two of the world’s major disruptions since 2020 – the coronavirus pandemic and the war in Ukraine. And yet, it should anger us. A new report by Greenpeace International, shows how 20 of the world’s biggest agribusiness corporations – the largest in the grain, fertiliser, meat and dairy sectors – exploited their outsized power to deliver obscene profits for shareholders while millions face food poverty and starvation.

The research, entitled ‘Food Injustice 2020-22: Unchecked, Unregulated and Unaccountable‘, shows a systemic failure of public policy, which has allowed a select group of multinational corporations to record huge profits, enriching the individuals that own them and transferring wealth to shareholders, of which the majority are located in the Global North. Adding up the 20 companies’ payments to shareholders in the financial years of 2020 and 2021 alone, reached the outrageous amount of $53.5 billion! To put this into context, in December of last year, the United Nations estimated that the amount needed in 2023 to save 230 million of the world’s most vulnerable people is $51.5 billion.

But how were they able to get their hands on this amount of money amid two major crises? By literally owning the market. Market concentration allows this small but inordinately powerful group of companies to have wildly disproportionate control, not only over the supply chains for food itself, but over information about those supply chains, which in turn allows for greater extraction of wealth to the benefit of their owners and shareholders, but to the detriment of you, me and everyone else. Cash dividends and shareholder buyback programmes allowed them to give an astronomical amount of money to their shareholders, while further amplifying their power over the sector’s industry and governments.

Let’s take the example of the grain industry: according to IPES, the four biggest companies in that sector, namely Archer-Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill and Dreyfus – also known by the acronym ABCD – “control 70-90% of the world’s grain trade, but are under no obligation to disclose what they know about global markets, including their own grain stocks”. This lack of transparency means that these companies withhold information that can shape grain prices according to their needs – not even hedge funds can get information other than directly from these companies. Our report finds that following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine opacity around the true amounts of grain in storage was a factor in the development of a speculative bubble.

There is no way out for governments and policy makers, but to take action. If we want to see a world without hunger – which is way overdue – the most impactful structural change we can make to the global food system is working to bring about food sovereignty.

For years, food sovereignty movements have sought to return autonomy back to food producers, shortening and strengthening supply chains to reverse the damage done by unsustainable farming, to communities, nature and our diets. And it is not just wishful thinking. From Papua New Guinea to Brazil, Mexico and many other countries, there are deep structural movements working to bring food into everyone’s plate.

Measures like universal basic income to help tackle poverty and redistribute wealth; taxing the windfall profits of corporations during crises with an ambitious and sector-wide windfall tax, and significant taxation on dividend payouts to wealthy stockholders as well as on income from dividends are just a few examples of the first steps governments must make to bring the prevailing food crisis to an end.

As one of the major topics during the latest UN conferences on climate and biodiversity, food has to be treated as a key component of human rights and climate change. Taking the power from those few corporations and returning it to small-scale ecological farmers is actively promoting the social justice we need to see in the contemporary world we are living in, but also facing climate crisis head-on! On a diplomatic level, governments can benefit from having more control over logistics and production and making cross-governmental decisions quicker and more efficiently to the benefit of the public.

It is time for food to be seen as what it is: a basic human need that has to be available to us all and not another commodity to be exploited and traded for the profit of a few families.

Davi Martins is a biodiversity campaign strategist at Greenpeace International