On the Radar: Tren de Aragua Is Not an International Drug Trafficking Group

We also lay out what it means that one of El Chapo’s ex-lawyers just got sworn in as a judge in Mexico, and dig into the future of criminal conflict between Guyana and Venezuela following an armed attack on the border between the two countries.

What Is Tren de Aragua?

President Donald Trump used the threat of Tren de Aragua during his successful campaign for the US presidency in 2024, citing the Venezuelan gang as an example of foreign criminal organizations threatening the United States. He used Tren de Aragua to strengthen his call for mass deportations.

*This article is the first in a nine-part investigation, “Tren de Aragua: Fact vs. Fiction,” analyzing the truth about the gang, as well as its evolution, current operations and how it may change in the future. Read the full investigation here.

Upon taking office in January, he wasted no time in declaring the Venezuelan gang, among others, a foreign terrorist organization, and “an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States.”

He followed this up in March by invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, a rarely used authority, to expedite the deportation of immigrants he alleged were members of Tren de Aragua. He insisted the Venezuelan gang was “perpetrating, attempting, and threatening an invasion of predatory incursion against the territory of the United States.”

Then in July the US Department of the Treasury sanctioned the leadership of Tren de Aragua, headed by Hector Rusthenford Guerrero Flores, alias “Niño Guerrero,” for whom a $5 million reward is offered, and Yohan Jose Romero, alias “Johan Petrica,” with a $4 million bounty. The statement insisted that Tren de Aragua “continues to expand.”

In August, the reward for information leading to the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro was raised to an unprecedented $50 million. US Attorney General Pam Bondi justified this record bounty by insisting that “Maduro uses foreign terrorist organizations like Tren de Aragua, the Sinaloa Cartel, and the Cartel of the Suns, to introduce lethal drugs and violence into our country.”

The claims about Tren de Aragua coming out of Venezuela could not be more different.

In July this year, Maduro stated at a police ceremony that Venezuela had “finished off Tren de Aragua.”

Last year, Venezuelan Foreign Minister Yván Gil declared that Tren de Aragua no longer existed.

“We have demonstrated that the Tren de Aragua is a fiction created by the international media to create a nonexistent label,” he said.

SEE ALSO: Tren de Aragua: From Prison Gang to Transnational Criminal Enterprise

These comments were off the back of declarations made by the Venezuelan Attorney General, Tarek William Saab, who said, “Tren de Aragua has been over-hyped and given a power that has never existed in reality … They have built a myth around Tren de Aragua … a matrix that seeks to link it to the Venezuela state.”

Cutting through the politicization of the issue, what do we know for certain about Tren de Aragua?

It was born as a prison gang in Tocorón jail in the Venezuelan state of Aragua. Venezuela’s prisons, once among the most violent in the world, spawned a series of criminal enterprises led by prison bosses known as “pranes.” Pran is an acronym for “preso rematado, asesino nato,” which translates into “hardened prisoner, born killer.” These gangs are referred to as the “pranato,” which spread through the prison system, encouraged by the Ministry of Popular Power for the Penitentiary Service (Ministerio del Poder Popular para el Servicio Penitenciario) in 2011, which sought to impose order in the prisons by handing over power to the pranes.

Tocorón prison saw the rise of a pranato led by Niño Guerrero, Johan Petrica, and Larry Amaury Álvarez, alias “Larry Changa.”

But these criminals were not content ruling the prison criminal fiefdom. They wanted to expand. The second stage of Tren de Aragua’s evolution was to spread outside the prison walls and set up a “megabanda,” or supergang, in the state of Aragua. Then, as prisoners affiliated to Tren de Aragua left prison after serving their sentences (or by escaping as in the case of Larry Changa) different criminal structures with links to Tren de Aragua began to appear across Venezuela. When Johan Petrica left Tocorón, he went south to the state of Bolívar and got involved in gold mining, taking over a local criminal mining gang called the Las Claritas Sindicato.

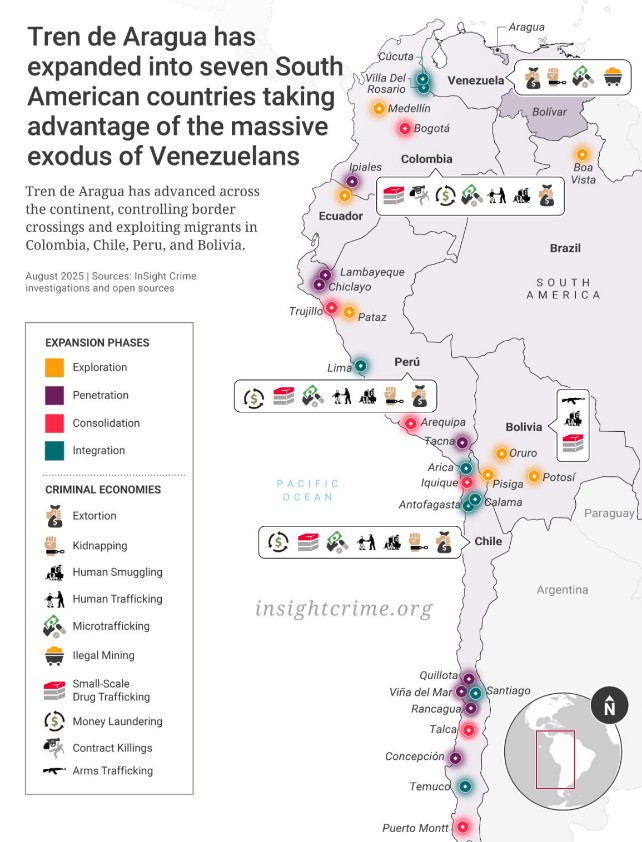

The nature of Tren de Aragua evolved once again amid Venezuela’s economic collapse, which sparked an exodus. To date almost eight million Venezuelans have fled the country in what has become one of the biggest refugee crises in the world, rivalling that of Syria. A small percentage of those fleeing Venezuela were criminals, who like their compatriots, were looking for better opportunities, including some, like Larry Changa, who were members of Tren de Aragua and had done time in Tocorón.

First these criminals preyed on their fellow Venezuelans as they traveled across South America looking for work, and then settled with them in nations like Colombia, Peru, and Chile, establishing human smuggling and trafficking networks, engaging in extortion and small-scale drug trafficking. When migration patterns switched in 2022, with Venezuelans heading in ever greater numbers for the United States, Venezuelan criminals accompanied them.

This was not some expansion that was planned from Tocorón. It happened organically. Almost none of the gangs abroad called themselves Tren de Aragua. However, the likes of Niño Guerrero, Johan Petrica, and Larry Changa soon realized the criminal potential of this expansion, and coordination began between different criminal elements. And when Tren de Aragua affiliated gangs abroad, like the Gallegos in Peru or Larry Changa’s in Chile, needed more manpower, or to link up with human smuggling networks in Colombia and Ecuador, they would reach out for reinforcements or contacts from Niño Guerrero in Tocorón.

This move abroad turned Tren de Aragua into a transnational criminal group, as recognized by the Biden administration in 2024. But by then Tren de Aragua was undergoing massive change as it lost its central hub and sanctuary.

by Jeremy McDermott 17 Aug 2025