Investors clutching cash might soon bear the brunt of a U.S. debt-ceiling fight, which could boil over in the next few weeks without a resolution.

Investors clutching cash might soon bear the brunt of a U.S. debt-ceiling fight, which could boil over in the next few weeks unless there’s a sudden resolution.

A previous deal by Congress suspended the U.S. debt limit through January 2025, after previously capping it at $36.1 trillion. While a last-minute deal in December was struck to avoid a government shutdown, it failed to eliminate the perennial debt-ceiling threat.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, in a late December letter to Congress, warned the U.S. could reach its new limit between Jan. 14 and Jan. 23, “at which time it will be necessary for Treasury to start taking extraordinary measures” to keep up with its bills and obligations.

“It’s going to be impactful,” said Deborah Cunningham, chief investment officer for global liquidity markets at Federated Hermes and a money-market industry veteran.

While there had been “some holdout hope” for Republican support for getting rid of the U.S. debt ceiling altogether, Cunningham’s team was bracing for extraordinary measures to take hold sometime in the last two weeks of January.

The clearest risk for investors resides in the massive Treasury bill market, a popular type of short-term government debt

TMUBMUSD01M

TMUBMUSD03M

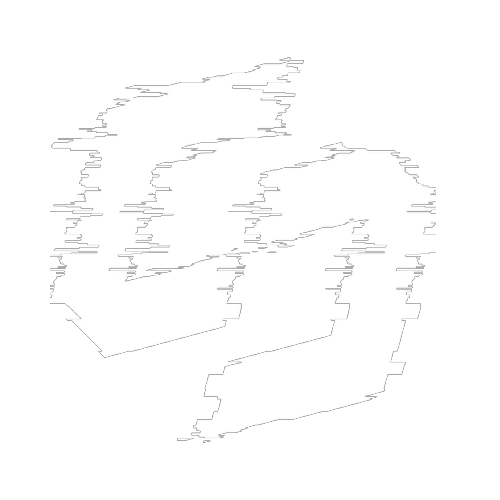

that matures in a year or less. The longer that disagreement over the borrowing limit drags out, the bigger the expected hit to issuance. The below chart shows bill supply turning negative in the past two debt-ceiling standoffs.

The debt-ceiling impasse could once again dry up T-bill issuance.Photo: Bank of New York Mellon Corp., Bloomberg, U.S. Treasury

Lower supply matters because T-bills have long been the lifeblood of the roughly $7 trillion money-market-fund industry, which has swollen from $4 trillion in 2020. Migration into these funds can be pegged to investors pulling cash out of bank-deposit accounts after several regional banks failed in 2023, but also to investors wanting to snap up higher 4% to 5% yields in money-market funds, which invest largely in T-bills, one of the world’s most liquid and safe investments.

While money-market funds can own several types of high-quality, short-term investments, none are as abundant as T-bills. Regulations also require the funds to hold assets that mature in 397 days or less, which limits what they can own. Yields, which move in the opposite direction as price, tend to fall when demand for certain assets increases.

Cunningham at Federated Hermes said the roughly $10 trillion investable market of T-bill supply for U.S. money-market funds could shrink by 30% to about $7 trillion in a scenario where the debt ceiling isn’t resolved.

“What that does to rates is challenging,” she said. “But ultimately, the impact of all portfolios is going to be marginally lower yields.”

What to expect next

Financial markets saw an explosive rally after the “red sweep” by Republicans in November’s election.

Yet longer-term rates used to finance the economy have shot up too, on concerns about the second Trump administration’s agenda of additional tax cuts, more tariffs, curtailing immigration and other “pro-growth” initiatives that could reignite inflation and add to the U.S. debt load.

Read: This fund manager forecast a 20% S&P 500 gain last year. Now he says cash is king.

President-elect Donald Trump in a Tuesday press briefing said the debt-ceiling fight wasn’t about “raising a lot of money. It’s really just about extending it. I just want to see an extension.”

While the fight plays out, financial markets have been operating without alarming signs of liquidity stress, even through the typical year-end crunch period, said Amar Reganti, fixed-income strategist with Hartford Funds.

Part of that, he said, was an expectation that the U.S. government could keep functioning under extraordinary measures until this summer, when the risk of a default, otherwise seen as unlikely, would become more pressing.

Meanwhile, the Treasury has a substantial cash balance at the Treasury General Account at the Federal Reserve, which in early January was around $677 billion. It was drawn down in the past two debt-ceiling disputes, adding to reserves in the financial system.

A related risk would be that once the debt-limit issue has been resolved, the subsequent “rebuild of the TGA” could quickly drain reserves from the system, “potentially creating volatility in funding markets at that time,” said John Velis, a Bank of New York Mellon Americas’ macro strategist, in a client note. Such stress also could imperil the Fed’s shrinking of its balance sheet, he said.

But despite “heartburn for capital markets” from past debt-ceiling disputes, as well as the tendency for Congress to wait until the “11th hour” to find a solution, the result consistently has been to raise the borrowing limit, Reganti at Hartford Funds said.

Still, it’s risk-averse investors, those helping to fund the government, who could shoulder the biggest hit.

By Victor Reklaitis contributed.