Economic experts have told The Independent the risk of a global recession remains despite the 90-day delay in Donald Trump’s aggressive tariff increases.

Trump made an abrupt U-turn on Wednesday when he announced the three-month pause to all affected countries bar China, following economic meltdown and widespread backlash.

But Pau S Pujolas, who wrote a study that was cited by the Trump administration to justify the tariff hikes, says the president’s “recklessness” means it may be too little, too late.

“Yes, the damage is done,” he said. “Global value chains are suffering with all the recklessness, uncertainty is a good friend of recession.

“This is not a serious way to manage an economy. Firms and households need clear, predictable policies to take the right decisions and make the economy blossom.”

Even if Trump decides not to reintroduce the high tariffs, the global economic risk remains “until either Trump stops playing the tariff game, or Congress removes the power vested on the president”, the associate professor at McMaster University in Canada added.

Economist Justin Wolfers agreed there would be lasting consequences despite the pause, as the president has shown he will say something one day and change his mind the next.

“The damage there is very, very lasting and very profound, because basically, he has shown he’s completely unreliable,” he told The Independent.

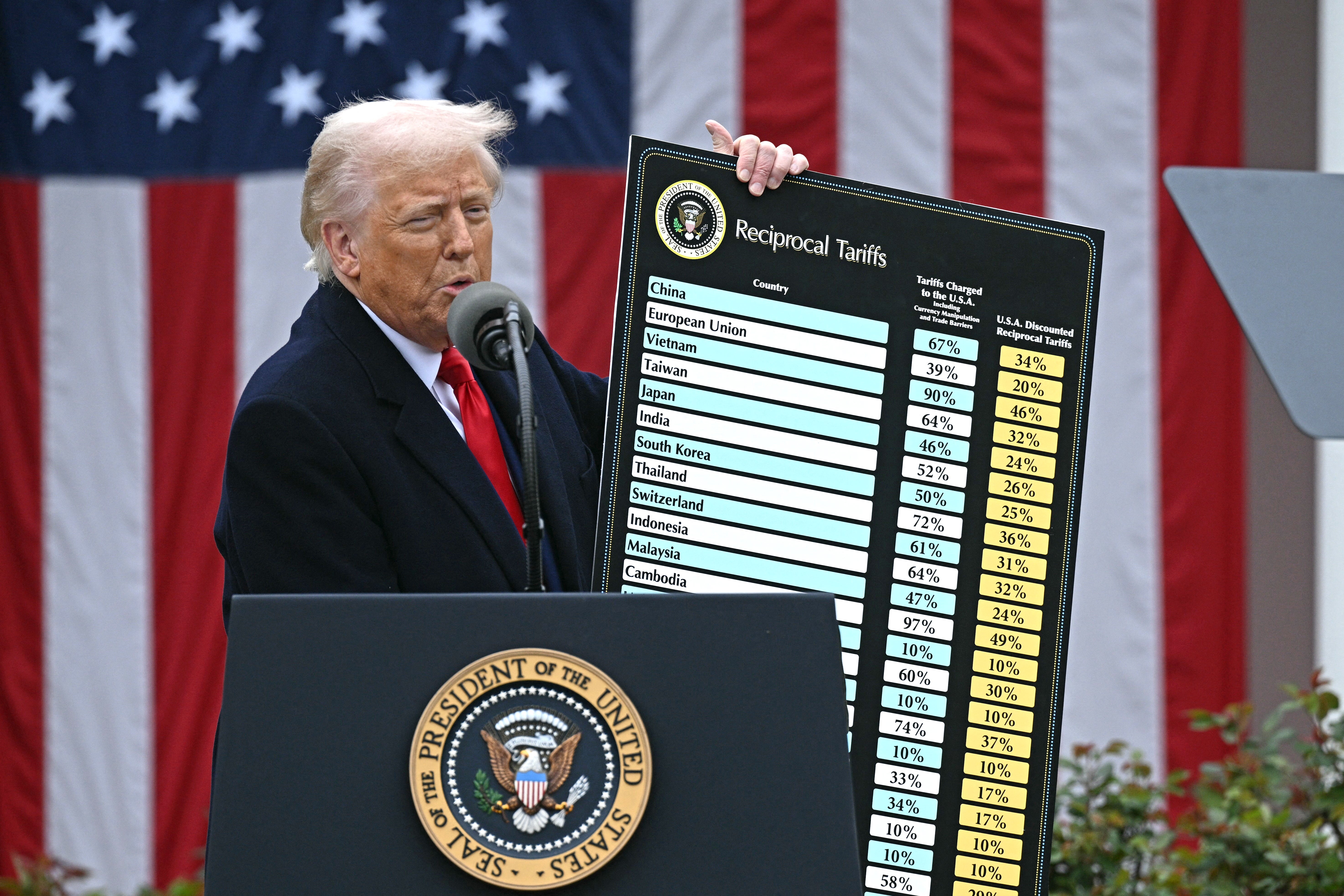

The Trump administration had announced aggressive tariff increases on nearly all of its trading partners, slapping levies of more than 30 per cent on some of the world’s weakest economies and placing a minimum tariff of 10 per cent on almost everyone else.

But after creating market turmoil, which was estimated to have wiped trillions off global stock markets by Tuesday, the president abruptly announced he would pause the hikes for 90 days, with the exception of the widespread 10 per cent levy, while also raising duties on China by an additional 125 per cent.

Wolfers, a professor of economics at the University of Michigan, said while pressing pause on the major levies had changed the risk of a global recession, it had done so “by less than you think”.

Even with the delay on tariffs of more than 30 per cent on some countries, with the previously increased tariffs on steel and cars, the US still has some of the highest tariffs in the world, he said.

“The tariff rate has fallen from maybe, you know, 20 times that of our trading partners, to be 15 times that of our trading partners. So it went from absurd to ridiculous,” he said.

Betting markets had recession odds at about 68 per cent on Wednesday morning, and those odds had fallen by Wednesday afternoon after the U-turn but were still at 53 per cent, Prof Wolfers said.

“It’s taken the edge off it, but it’s only taken the edge off. So the risks remain incredibly elevated,” he said.

Leading independent Australian economist Chris Richardson said the risk of a recession remains elevated because the constant mind-changing was terrible for long-term business planning and public sector decision-making.

“Chaos comes at a cost, and the tariff stuff is playing out to the tune of ‘Hokey Pokey’. Tariffs go on, tariffs go off, then get shaken all about,” he said.

The constant change in America’s trade policy has also made the people who lend money to financial markets nervous, he said, as evidenced by the fall in the US bond market.

“What’s happening with the Trump stuff is the world is seeing risks going up, and people choosing to be safer: less risk, less return,” he added.

Dan Coatsworth, investment analyst at AJ Bell, said the past week of uncertainty alone could have already had “a major negative impact on spending” and hurt economies, but that uncertainty was continuing.

“The risk of a global recession remains high until there is more clarity on tariffs longer term,” he said. “Countries on the receiving end of US tariffs are still negotiating deals, and a 10 per cent baseline tariff during the 90-day ‘pause’ period means we aren’t back to how the world worked pre-Liberation Day.”

Bernard Yaros, lead US economist at Oxford Economics, said all these questions will “reinforce a ‘wait and see’ attitude among households and firms”.

“The longer the uncertainty persists, the weaker consumer spending and business investment will be,” he said.

Richardson said the escalating tariff war between China and the US will also have broader ramifications, and the longer that continues, the more people elsewhere will feel its negative effects.

“We’re not necessarily going to see big problems off the back of this yet, but the longer it lingers, the greater the risk,” he said.

Coatsworth echoed that sentiment, saying the trade relationship between the US and China was “in tatters”.

“It is now significantly more expensive for a US company to buy goods from China, and for Chinese companies to buy from the US,” he added. “The end customer will ultimately bear the extra cost and they could vote with their feet by buying less or not at all.”