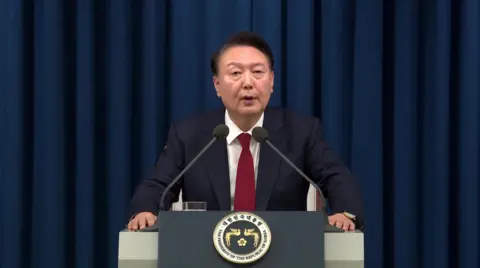

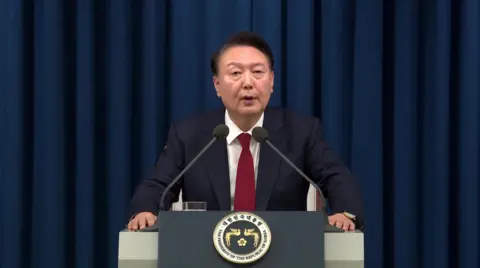

Under mounting political pressure, South Korea’s President Yoon Suk Yeol on Tuesday night declared martial law in the democratic country for the first time in nearly 50 years.

His late-night pronouncement, made on national TV at 23:00 local time (14:00 GMT), mentioned national security and the threat from North Korea, but it soon became clear Yoon had made this drastic move in response to a series of political setbacks.

He was driven to the point of invoking martial law – temporary rule by the military – as a tactic to fend off the political attacks, observers say.

But it triggered immediate protests outside parliament and lawmakers voted down the measure, which they said was illegal, within hours.

How did it unfold?

After referring to the opposition’s political attacks, President Yoon on Tuesday night said he was declaring martial law to “crush anti-state forces that have been wreaking havoc”.

That put the military in charge temporarily – triggering the deployment of troops and police to parliament where helicopters were seen landing on the National Assembly’s roof.

The military also issued a decree banning protests and activity by parliament and political groups, and putting media under government control.

But South Korea’s political opposition immediately called Yoon’s declaration illegal and unconstitutional. The leader of Yoon’s own party, the conservative People’s Power Party, also called his act “the wrong move”.

Meanwhile, main opposition leader Lee Jae-myung called on his Democratic Party MPs to converge on the parliament to vote down the declaration.

He also called on ordinary South Koreans to show up at parliament in protest.

“Tanks, armoured personnel carriers and soldiers with guns and knives will rule the country… My fellow citizens, please come to the National Assembly.”

Hundreds heeded the call, rushing to gather outside the heavily- guarded parliament. Crowds of protesters chanted: “No martial law! No martial law.”

Local media broadcasting from the site showed some scuffles between protesters and police at the gates. But despite the heavy military presence, the tensions did not escalate into violence.

And lawmakers were also able to make their way around the barricades to get into the parliamentary voting chambers.

Shortly after 01:00 Wednesday local time, South Korea’s parliament, with 190 of its 300 members present, voted down the measure. President Yoon’s declaration of martial law was ruled invalid.

How significant is martial law?

Martial law is temporary rule by military authorities in a time of emergency, when civil authorities are deemed unable to function.

The last time it was declared in South Korea was in 1979, when the country’s then long-term military dictator Park Chung-hee was assassinated during a coup.

It has never been invoked since the country became a parliamentary democracy in 1987.

But on Tuesday, Yoon pulled that trigger, saying in a national address he was trying to save South Korea from “anti-state forces”.

Yoon, who has taken a noticeably more hardline stance on North Korea than his predecessors, described the political opposition as North Korea sympathisers – without giving any evidence.

Under martial law, extra powers are given to the military and there is often a suspension of civil rights for citizens and rule of law standards and protections.

What has fired up the opposition?

Yoon was voted into office in May 2022, but has been a lame duck president since April when the opposition won a landslide in the country’s general election.

His government since then has not been able to pass the bills they wanted and have been reduced instead to vetoing bills passed by the opposition.

He has also seen a fall in voter standing, having been mired in several corruption scandals – including one involving the First Lady accepting a Dior bag, and another around stock manipulation.

Just last month he was forced to issue an apology on national TV, saying he was setting up an office overseeing the First Lady’s duties. But he rejected a wider investigation, which opposition parties had been calling for.

Then this week, the opposition proposed slashing budgets for his government – and budget bills cannot be vetoed.

At the same time, the opposition also moved to impeach cabinet members and several top prosecutors- including the head of the government’s audit agency – for failing to investigate the First Lady.

What now?

Yoon’s declaration caught many off guard – and it has been a fast-moving situation these past hours.

But the opposition was able to congregate quickly at parliament and had the numbers to vote down the martial law declaration.

And despite the heavy presence of troops and police in the capital, a takeover by the military has, it seems, not materialised.

Under South Korean law, the government must lift martial law if a majority in parliament demands it in a vote.

The same law also prohibits martial law command from arresting lawmakers.

It’s unclear what happens now. Some of the protesters gathered outside the assembly on Tuesday night had also been shouting: “Arrest Yoon Suk Yeol”.

But President Yoon’s rash action has stunned the country – which views itself as a thriving, modern democracy that has come far since its dictatorship days.

This is being viewed as the biggest challenge to that democratic society in decades.

As the speaker of parliament said on Wednesday: “We will protect democracy together with the people.”