Will Grant

BBC Mexico correspondent

In the shadow of a vast crucifix, labourers and construction workers in the Mexican border city of Ciudad Juarez are building a small city of their own. A tent city.

On the old fairgrounds, beneath an altar constructed for a mass by Pope Francis in 2016, the Mexican government is preparing for thousands of deportees they expect to arrive from the United States in the coming weeks.

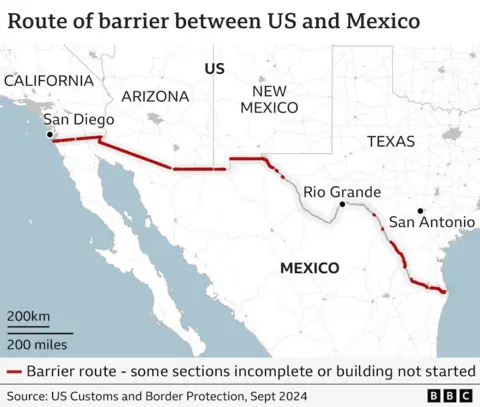

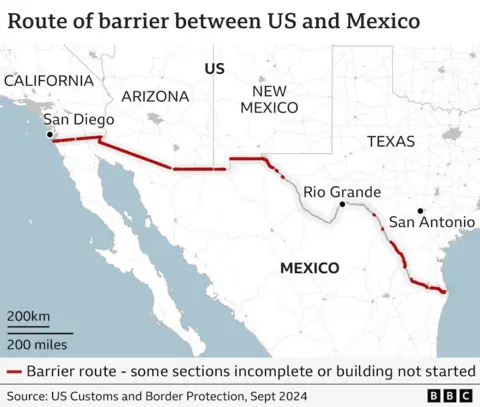

Juarez is one of eight border locations along the 3,000-kilometre-long (1,900 miles) border where Mexico is getting ready for the anticipated influx.

Reuters

ReutersMen in boots and baseball caps climb on top of a vast metal structure to drape over thick white tarpaulin, erecting a rudimentary shelter to temporarily house men and women exactly like themselves.

Casual labourers, domestic workers, kitchen staff and farm hands are all likely to be among those sent south soon, once what President Donald Trump calls “the largest deportation in American history” gets under way.

As well as protection from the elements, the deportees will receive food, medical care, and assistance in obtaining Mexican identity documents, under a deportee-support programme which President Claudia Sheinbaum’s administration calls “Mexico Embraces You”.

“Mexico will do everything necessary to care for its compatriots and will allocate whatever is necessary to receive those who are repatriated,” said the Mexican Interior Minister, Rosa Icela Rodriguez, on the day of Trump’s inauguration.

For her part, President Sheinbaum has stressed her government will first attend to the humanitarian needs of those returning, saying they will qualify for her government’s social programmes and pensions, and will immediately be eligible to work.

She urged Mexicans to “remain calm and keep a cool head” about relations with President Trump and his administration more broadly – from deportations to the threat of tariffs.

“With Mexico, I think we are going very well,” said President Trump in a video address to the World Economic Forum in Davos this week. The two neighbours may yet find a workable solution on immigration which is acceptable to both – President Sheinbaum has said the key is dialogue and keeping the channels of communication open.

Undoubtedly, though, she recognises the potential stress President Trump’s declaration of an emergency at the US border could place on Mexico.

An estimated 5 million undocumented Mexicans currently live in the United States and the prospect of a mass return could quickly saturate and overwhelm border cities like Juarez and Tijuana.

It’s an issue which worries Jose Maria Garcia Lara, the director of the Juventud 2000 migrant shelter in Tijuana. As he shows me around the facility, which is already nearing its capacity, he says there are very few places he can fit more families.

“If we have to, we can maybe put some people in the kitchen or the library,” he says.

There comes a point, though, where there simply isn’t any space left – and donations of food, medical supplies, blankets and hygiene products will be stretched too thin.

“We’re being hit on two fronts. Firstly, the arrival of Mexicans and other migrants who are fleeing violence,” says Mr Garcia.

“But also, we’ll have the mass deportations. We don’t know how many people will come across the border needing our help. Together, these two things could create a huge problem.”

Furthermore, another key part of Mr Trump’s executive orders includes a policy called “Remain in Mexico” under which immigrants awaiting dates to make their asylum cases in a US immigration court would have to stay in Mexico ahead of those appointments.

When “Remain in Mexico” was previously in place, during Trump’s first term and under the presidency of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador in Mexico, Mexican border towns struggled to cope.

Human rights groups also repeatedly denounced the risks the migrants were being exposed to by being forced to wait in dangerous cities where drug cartel-related crime is rife.

This time around, Sheinbaum has made it clear that Mexico has not agreed to the plan and won’t accept any non-Mexican asylum seekers from the US as they wait for their asylum hearings. Clearly, “Remain in Mexico” only works if Mexico is willing to comply with it. So far, it has drawn a line.

President Trump has deployed around 2,500 troops to the US southern border where they will be tasked with carrying out some of the logistics of his crackdown.

In Tijuana, meanwhile, Mexican soldiers are helping to prepare for the consequences of it. The authorities have readied an events centre called Flamingos with 1,800 beds for the returnees and troops bringing in supplies, setting up a kitchen and showers.

As President Trump was signing executive orders on Monday, a minibus swept through the gates at the Chaparral border crossing between San Diego and Tijuana carrying a handful of deportees.

A few journalists had gathered to try to speak to, ostensibly, the first deportees of the Trump era. It was just a routine deportation, though, one which was probably in the pipeline for weeks and had nothing to do with the documents Trump was signing before a cheering crowd in Washington DC.

Still, symbolically, as the minibus sped past the waiting media towards a government-run shelter, these were the first of many.

Mexico will have its work cut out to receive them, house them and find them a place in a nation some won’t have seen since they left as children.