[ad_1]

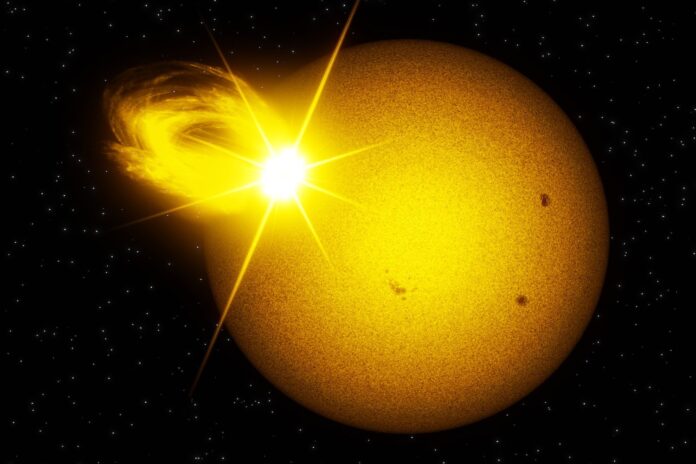

Earlier this year, Earth experienced two geomagnetic storms caused by outbursts of radiation from the Sun, which had an impact on satellites in space and communication systems on the ground. As it turns out, the Sun may be capable of much more powerful solar flares.

The Sun is a giant glowing ball of plasma that keeps our solar system together, but there are billions of stars like it spread out across the cosmos. Although scientists have only been studying the Sun up close for the past 60 years or so, monitoring Sun-like stars in different stages of their lifetime can help predict the behavior of Earth’s host star. Hoping to find out whether the Sun is capable of producing superflares, which are thousands of times more powerful than a solar flare, a team of scientists pored over data of 56,000 Sun-like stars. The team identified 2,889 superflares on 2,527 of the stars, indicating that stars with similar temperatures and variability as our Sun produce superflares roughly once per century.

So far, scientists remain unsure about whether or not the Sun is capable of producing a superflare as no such event has been recorded on our host star. Extreme solar activity in the past has left its mark on Earth in the form of isotope spikes, but these events fall short of the energy levels expected from a superflare, according to the research. That said, the findings, published today in the journal Science, not only give scientists a better understanding of our host star, but could also help them better predict upcoming geomagnetic storms that mess with our technology on Earth.

“We wanted to determine how often our Sun produces superflares; however, the duration of direct solar observations is relatively short,” Valeriy Vasilyev, from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, and lead author of the new study, told Gizmodo.

Instead of relying on observations of the Sun, the researchers behind the study turned to data collected by NASA’s Kepler space telescope, which scoured the cosmos for exoplanets during its nine years in space. “An alternative approach is to analyze the extensive data collected by space telescopes like Kepler…by observing approximately 56,000 Sun-like stars over a span of four years, we effectively accumulated the equivalent of around 220,000 years of solar observations,” Vasilyev added.

The findings also revealed that the frequency of superflares aligns with previously observed solar flare patterns from the Sun, suggesting a shared underlying mechanism. A regular solar flare—giant explosions on the Sun that fling high speed particles into space—emits an equivalent of ten million times the energy released by a volcanic eruption on Earth. Superflares, on the other hand, are 10,000 times more powerful than solar flares.

Flares are a natural phenomena of solar activity. The Sun follows an 11-year cycle that influences its level of solar activity. This year, NASA confirmed that the Sun is in its solar maximum, a period of increased activity marked by intense solar flares and coronal mass ejections. In May, a G5, or extreme, geomagnetic storm hit Earth as a result of large expulsions of plasma from the Sun’s corona (also known as coronal mass ejections). The G5 storm, the first to hit Earth in more than 20 years, caused some deleterious effects on Earth’s power grid and resulted in thousands of satellites shifting position in low Earth orbit.

“If accompanied by a coronal mass ejection (CME), [a superflare] could lead to extreme geomagnetic storms on Earth,” Vasilyev said. “Such storms may severely disrupt technological systems.”

The researcher noted that further detailed investigations are required to determine if the observed stars differ from the Sun, or if their activity reflect our host star’s future potential. The Sun is considered a typical yellow dwarf star. However, it was recently discovered that the Sun exhibits a much lower brightness variability compared to other Sun-like stars in the Kepler telescope field of view, according to Vasilyev. “This indicates that the Sun is less active than most solar analogs,” Vasilyev added.

The study accounted for this factor by including a larger and more representative sample of Sun-like stars, but it’s not clear whether that would affect the Sun’s ability to produce superflares like its stellar counterparts.

[ad_2]

Source link